- Home

- Child, Lee; Bruen, Ken

First Thrills: Volume 2 Page 2

First Thrills: Volume 2 Read online

Page 2

Solo used a small flashlight to inspect the cockpit compartment, then the instrument panel. There were no conventional gauges, merely flat planes where presumably information from the ship’s computers was displayed. There were a few mechanical switches mounted on one panel, but only a few.

Lying carelessly on the panel, where the impact of the crash or the jostling of salvage had carried them, were two headbands, almost an inch wide, capable of being easily expanded to give the wearer a tight fit.

Hope flooded him. At first glance the ship seemed intact. If only the computers and communications systems are in order!

Solo was still standing rooted in his tracks, taking it all in, when Jim Bob Bryant crawled up through the entry and closed the hatch behind him. As he looked around, he said something under the breathing mask that Solo didn’t understand. Solo slowly removed his own mask and laid it on the instrument panel.

Bryant kept glancing at Solo, the mine canary, for almost a minute as he tried to take in his surroundings. Then he removed his mask, too, and stood looking around like a lucky Kmart shopper.

“Amazing,” he said under his breath, then said it again, louder. He reached out to touch things.

Solo moved the flashlight beam around the interior of the ship, inspecting for damage. The cockpit was so Spartan that there was little to damage.

“Does it look like that one the government has in Nevada?” Bryant asked.

“Very similar,” Solo said, nodding.

“Where is the crew? How did they get out with this thing in the ocean?”

Solo took his time answering. “Obviously the crew wasn’t in the saucer when it submerged. I can’t explain it, but that is the only logical explanation.” The flashlight beam continued to rove, pausing here and there for a closer inspection.

“Reverend Bryant, I know you’ve had a long day and have much to think about,” Solo continued. “My examination of the ship will go much faster if you leave me to work in solitude.”

Bryant beamed at Solo. “I didn’t think it could be done,” he admitted. “When you told me you could raise this ship and wring out its secrets, I thought you were lying. I want you to know I was wrong. I admit it, here and now.”

Solo smiled.

“I leave you to it,” Bryant said. “If you will just open that hatch to let me out.” He took a last glance around. “Simply amazing,” he muttered.

Solo opened the hatch and Bryant carefully climbed through, then Solo closed it again.

Alone at last, Solo’s face relaxed into a wide grin. He stood beside the pilot’s seat, grinning happily, apparently lost in thought.

Finally he came out of his reverie and walked to the back of the compartment, where he opened an access door to the engineering compartment and disappeared inside. He was inside there for an hour before he came out. For the first time, he retrieved a headband from the instrument panel and donned it.

“Hello, Eternal Wanderer. Let us examine the health of your systems.”

Before him, the instrument panel exploded into life.

* * *

The first mate DeVries strolled along the bridge with the helm on autopilot. The rest of the small crew, including the captain, were in their bunks asleep. The rain had stopped and a sliver of moon was peeping through the clouds overhead. The mate had always enjoyed the ethereal beauty of the night and the way the ship rode the restless, living sea. He was soaking in the sensations, occasionally crossing the bridge from one wing to the other, and checking on the radar and compass, when he noticed the glow from the saucer’s cockpit.

The space ship took up so much of the deck that the cockpit canopy was almost even with the bridge windows. As the mate stared into the cockpit, he saw the figure of Adam Solo. He reached for the bridge binoculars. Turned the focus wheel.

Solo’s face appeared, lit by a subdued light source in front of him. The mate assumed that the light came from the instruments—computer presentations—and he was correct. DeVries could see the headband, which looked exactly like the kind the Indians wore in old cowboy movies. Solo’s face was expressionless … no, that wasn’t true, the mate decided. He was concentrating intensely.

Obviously the saucer was more or less intact or it wouldn’t have electrical power. Whoever designed that thing sure knew what he was about. He or she. Or it. Whoever that was, wherever that was …

Finally the mate’s arms tired and he lowered the binoculars.

He snapped the binoculars into their bracket and went back to pacing the bridge. His eyes were repeatedly drawn to the saucer’s glowing cockpit. The moon, the clouds racing overhead, the ship pitching and rolling monotonously—it seemed as if he were trapped in this moment in time and this was all there had ever been or ever would be. It was a curious feeling … almost mystical.

Surprised at his own thoughts, DeVries shook his head and tried to concentrate on his duties.

* * *

This is Eternal Wanderer. I am Adam Solo. Is there anyone out there listening?

Solo didn’t speak the words, he merely thought them. The computer read the tiny impulses as they coursed through his brain, boosted the wattage a billionfold, and broadcasted them into the universe. Yet the thoughts could only travel at the speed of light, so unless there was an interplanetary ship, or a saucer relatively close in space, he might receive no answer for years. Decades. Centuries, perhaps.

Marooned on this savage planet, he had waited so long! So very long.

Solo wiped the perspiration from his forehead as the enormity of the years threatened to reduce him to despair.

He forced himself to take off the headband and leave the pilot’s seat.

Opening the saucer’s hatch, he dropped to the deck. He closed the hatch behind him, just in case, and went below to his cabin. No one was in the passageways. Nor did he expect to find any of the crew there. He glanced into one of the crew’s berthing spaces. The glow of the tiny red lights revealed that every bunk was full, and every man seemed to be snoring. They had had an exhausting day raising the saucer from the seabed.

In his cabin Solo quickly packed his bag. He stripped the blankets from his bunk and, carrying the lot, went back up on deck. Careful to stay out of sight of the bridge, he stowed his gear in the saucer.

A hose lay coiled near a water faucet, one the crew routinely used to wash mud from cables and chains coming aboard. Solo looked at it, then shook his head. The water intake was on top of the saucer; climbing up there would expose him to the man on the bridge, and would be dangerous besides. He couldn’t risk falling overboard, which would doom him to inevitable drowning—certainly not now. Not when he was this close.

He removed the tie-down chains one by one and lowered them gently to the deck so the sound wouldn’t reverberate through the steel ship.

Finally, when he had the last one off, he stood beside the saucer, with it between him and the bridge, and studied the position of the crane and hook, the mast and guy wires. Satisfied, Adam Solo stooped, went under the saucer, and up through the hatch.

* * *

The first mate was checking the GPS position and the recommended course to Sandy Hook when he felt the subtle change in the ship’s motion. An old hand at sea, he noticed it immediately and looked around.

The saucer was there, immediately in front of the bridge. But it was higher, the lighted canopy several feet above where it had previously been. He could see Solo’s head, now seated in the pilot’s chair. And the saucer was moving, rocking back and forth. Actually it was stationary—the ship was moving in the seaway.

DeVries’s first impression was that the ship’s motion had changed because the saucer’s weight was gone, but he was wrong. The antigravity rings in the saucer had pushed it away from the ship, which still supported the entire mass of the machine. The center of gravity was higher, so consequently the ship rolled with more authority.

At that moment Jim Bob Bryant came up the ladder, moving carefully with a cup of coffee in his hand.<

br />

He saw DeVries staring out the bridge windows, transfixed.

Bryant turned to follow DeVries’s gaze, and found himself looking at Adam Solo’s head inside the saucer. Solo was too engrossed in what he was doing to even glance at the bridge. The optical illusion that made the saucer appear to be moving gave Bryant the shock of his life. Never, in his wildest imaginings, had he even considered the possibility that the saucer might be capable of flight.

Like DeVries, Bryant stood frozen with his mouth agape.

For only a few more seconds was the saucer suspended over the deck. As the salvage ship came back to an even keel the saucer moved toward the starboard side, rolling the ship dangerously in that direction. Then the saucer went over the rail and the ship, free of the saucer’s weight, and rolled port with authority.

Bryant recovered from his astonishment and roared, “No! No, no no! Come back here, Solo! It’s mine. Mine, I tell you, mine!”

He dropped his coffee cup and strode to the door that led to the wing of the bridge, flung it open, and stepped out. The mate was right behind him. Both men grabbed the rail with both hands as the wind and sea spray tore at them.

The lighted canopy was no longer visible. For a few seconds Bryant and DeVries could see a glint of moonlight reflecting off the dark upper surface of the departing spaceship; then they lost it. The night swallowed the saucer.

It was gone, as if it had never been.

“If that doesn’t take the cake!” exclaimed the Reverend Jim Bob Bryant. “The bastard stole it!”

* * *

“Adam, this is Star Voyager. So good to hear from you.”

“I am alive. I have a saucer. I can meet you above the savage planet.”

The voice from the starship told him when their ship would reach orbit. Solo mentally converted the time units into earth weeks. Three weeks, he thought. Only three more weeks.

“I must pick up the others,” he thought, and the com system broadcast these thoughts.

Adam Solo topped the cloud layer that shrouded the sea and found himself under a sky full of stars.

* * *

STEPHEN COONTS is the author of fifteen New York Times bestsellers, the first of which was the classic flying tale Flight of the Intruder.

Stephen received his Navy wings in August 1969. After completion of fleet replacement training in the A-6 Intruder aircraft, Mr. Coonts reported to Attack Squadron 196 at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Washington. He made two combat cruises aboard USS Enterprise during the final years of the Vietnam War as a member of this squadron. His first novel, Flight of the Intruder, published in September 1986 by the Naval Institute Press, spent twenty-eight weeks on The New York Times bestseller lists in hardcover. A motion picture based on this novel, with the same title, was released nationwide in January 1991. The success of his first novel allowed Mr. Coonts to devote himself to writing full-time; he has been at it ever since. He and his wife, Deborah, enjoy flying and try to do as much of it as possible.

When Johnny Comes Marching Home

HEATHER GRAHAM

It was eighteen sixty-five when the terror came to Douglas Island.

Eighteen sixty-five when Johnny came home.

Naturally, it was a time when few people cared what was happening on a small, barely inhabited southern island off the coast of South Carolina.

So much tragedy had already come to the country; there were so many dead, dying, maimed, and left without home or sustenance that a strange plague descending upon a distanced population was hardly of note.

Unless you were there, unless you saw, and prayed not just for your life, but your soul.

The war was over, but not the bitterness. Lincoln had been assassinated, and all hope of a loving and swift reunion between the states had been dashed.

Brent Haywood, Johnny’s cousin, had made it home the week before. A government ship—a Federal government ship—had brought him straight to the docks. He limped. He was often in pain. Shrapnel had caught him in the right hip, and he’d be in pain, limping, for the rest of his life.

Brent had been a prisoner a long time, and he told me that he hadn’t seen Johnny since Cold Harbor, and that he wasn’t sure if he wanted to see Johnny; he hadn’t known that his cousin had survived until we had received the news. “There’s something not—right with Johnny,” he told me.

The world, our world, or that of our country, was in a sad way, desperately sad. On Douglas Island, we had survived many years of the travelers who had come from far and wide to see the beauty of our little place, to ride over the sloping hills, to fish and boat and hunt. The war had barely begun before we had ceased to care who won or lost. Now, far too many people were struggling just to survive. The South was in chaos.

And so it was on the day that Johnny MacFarlane came home.

At first, nearly the whole town came out, two hundred odd of us came to the docks to meet the boat that had brought him home. A letter had been received the previous week, and we knew just when the schooner the Chesapeake was to bring him home. A kindly surgeon Johnny had come upon somewhere in his travels home after the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse had written that Johnny MacFarlane was not well, but friends were helping and would be sending him home with all possible speed, and they made arrangements for his travel.

Came the day. I was there with my father, eager, barely able to wait through the moments that would bring him back to me. From the widow’s walk of Johnny’s home, Janey Sue, his sister, had seen the schooner out on the horizon, and so we had gathered. Our town band was playing welcome songs, and it was no matter that he’d been one of the last battered soldiers of Lee’s army, we were one country now, and the band played for him, using all the songs we knew. People sang at the docks, and it was momentous. Federal song, fine. They played, “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.”

Except that the schooner stopped far out to sea, and it was strange, for even the music ended by the time Johnny rowed himself to shore in a small boat.

There was deep dockage at the island, and throughout the war, we’d been visited now and then by ships from both sides, and it was only the fact that we were, actually, so small and seeming to offer so little in support or importance that they all passed us by with little interest after docking. Sometimes, sailors wanted to loot the houses, but thanks to my father’s brilliance at hiding all assets, they did not stay. We had never imagined that any ship would eschew the fine docks and send Johnny home in a longboat, but so they did.

No matter.

Johnny was coming home.

And we watched as he rowed, and we waited until the little boat reached the docks, and then we all raced to him, descended upon him, really, tying up the rowboat, and helping him to the dock. His dear little sister, Janey Sue, immediately threw herself into his arms, nearly knocking him from the dock.

He hugged her in return; over her shoulder, he looked at me.

I was shocked.

Johnny and I had been together forever. We’d both been born and raised on the island. We had dreamed great visions for our future, and in those dreams, we would travel, but always return to our island. He wanted to be a teacher. Knowledge gave a man power and strength, he believed. Oh, Johnny had always been a thinker, and I had loved following the processes in his mind.

But he’d been more than a thinker. Johnny had been a doer, a man who had always been strong, in a way, the typical Southern gentleman of his age. He could drink, ride, and shoot with the best of them, and also been able to repair any leak or damage done to Fairhaven, his estate on the island.

He was a man ahead of his time; he had joined the Confederate forces because he had believed in states rights. He had never believed in slavery—how could one human being, one soul, ever own another?—but he had also believed that change had to come about with laws that would help newly freed individuals make a living—survive, in short.

He had been … Johnny. Beautiful, such a handsome man. Smart, always careful in his thoughts

and words. Strong, a man’s man, a woman’s man, independent, powerful, capable.

And now.…

Johnny was a shell of the man he had been. My father had warned me—war changed people. It brought out their strengths and their weaknesses, but either way, it changed a man for good. We had heard that Lee’s troops had been starving, so his emaciated shape shouldn’t have shocked me. His pallor had come about, certainly, because of his illness.

But I had never expected the look in his eyes.

Once, they had been the blue of the sky on a summer’s day, as brilliant and vital as Johnny himself. Once … they had brightened easily with laughter. Once upon a time, they had looked at me in way that had awakened every raw and erotic thought in my mind, and stirred my heart to a thunderous pounding. Once.…

They had been alive.

He looked at me now with recognition, but even the color in his eyes had changed. Now, they seemed so pale a blue as to be almost colorless.

It was as if … the color within them was dead. It was a ghost color, like the remnant of what had once been real and tangible, but now was nothing more than a memory.

I gave myself a shake. The town was welcoming him, but as he looked at me over his sister’s shoulder, he smiled slowly. A ghost of his old smile, but it was there, and suddenly, as dead as his eyes might appear, I saw that he had never forgotten what we had shared, that he loved me. I told myself that I was crazy. I rushed forward through the crowds, and he took me into his arms. Despite his fragile appearance, he swept me up in strong arms and swirled me around, and held me close.

“Now,” he whispered, “I have come home.”

I smiled at him; I was jubilant. Johnny was home.

* * *

Once he had been greeted by one and all, we helped him into the family carriage and headed to his home, Fairhaven. We were greeted at the door by Brambles, the butler, while in the foyer stood Brent, who had not come to the docks to meet Johnny. Brambles was all over himself, sputtering and crying as he greeted Johnny. Brent was more reserved, shaking his cousin’s hand. He was cordial, but visibly cool. Johnny was polite to everyone, saying all the right things.

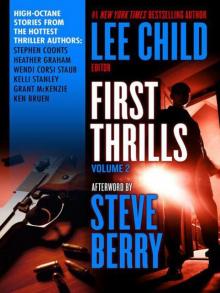

First Thrills: Volume 2

First Thrills: Volume 2